Ethnicity and Drug Response: How Genetics Affect Medication Effectiveness

When you take a pill, your body doesn’t just absorb it the same way everyone else does. Your ethnicity and drug response, how your genetic background influences how medications are absorbed, broken down, and cleared from your body can change everything—from whether a drug works at all to whether it causes dangerous side effects. This isn’t guesswork. It’s biology. And it’s why two people with the same diagnosis can need completely different doses—or even different drugs—to get the same result.

The science behind this is called pharmacogenomics, the study of how genes affect a person’s response to drugs. For example, people of East Asian descent often metabolize the blood thinner warfarin more slowly, meaning they need much lower doses to avoid bleeding risks. Meanwhile, African Americans with high blood pressure often respond better to calcium channel blockers than to ACE inhibitors, a difference tied to genetic variations in kidney function and salt regulation. These aren’t random trends—they’re patterns backed by decades of clinical data and FDA warnings.

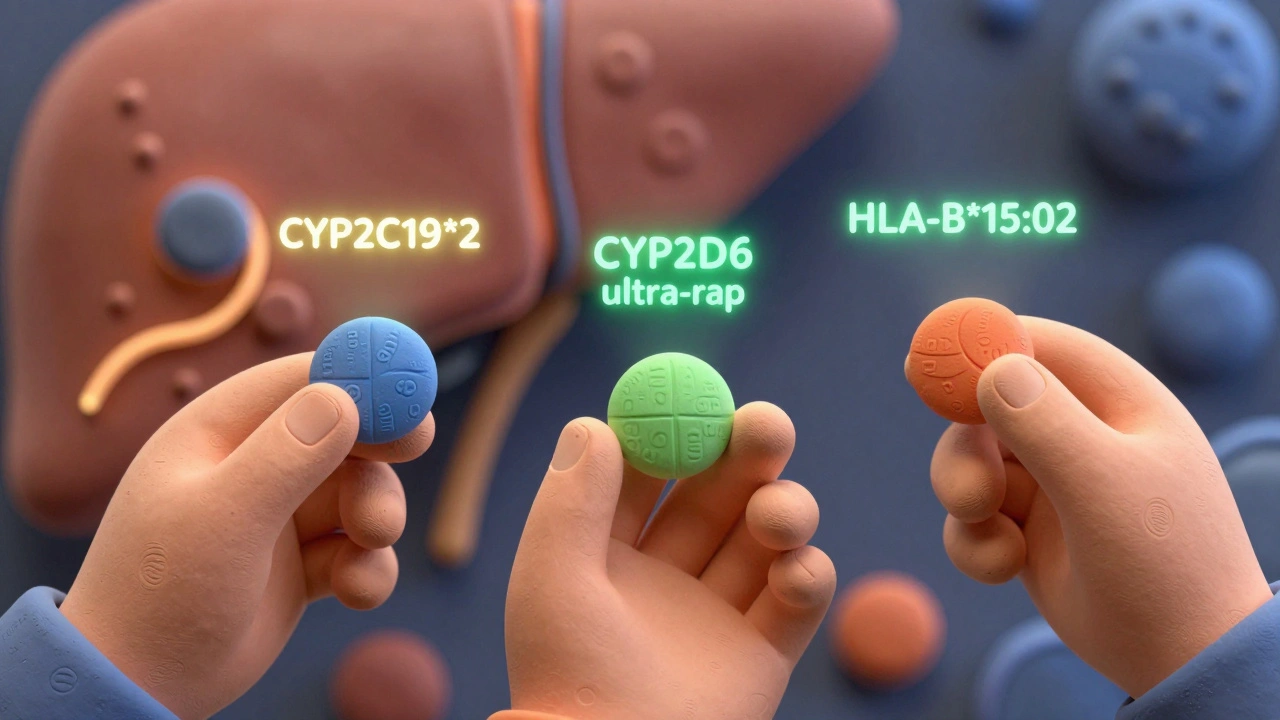

It’s not just about race or geography. It’s about inherited enzyme activity. The CYP2D6 gene, for instance, controls how over 25% of common drugs are processed. Some people have extra copies of this gene (ultra-rapid metabolizers), meaning drugs like codeine get turned into morphine too fast—risking overdose. Others have little to no activity (poor metabolizers), so the drug just sits there, useless. These variations show up differently across populations. One study found that 1 in 10 people of European descent are poor metabolizers of CYP2D6, while only 1 in 50 of East Asians are. That’s a massive difference in how safe or effective a drug will be.

And it’s not just about effectiveness. Side effects vary too. The heart rhythm drug amiodarone causes more thyroid problems in people of European descent. The antibiotic linezolid triggers more nerve damage in African populations. Even something as simple as the painkiller codeine can be deadly in babies of mothers who are ultra-rapid metabolizers—something now flagged in FDA safety alerts.

What does this mean for you? If you’ve ever been told a medication didn’t work for you—or gave you side effects others didn’t get—it might not be you. It might be your genes. And while genetic testing isn’t routine yet, doctors are starting to use ancestry and population data to make smarter choices. A doctor treating someone with African ancestry might skip a standard beta-blocker and go straight to a diuretic. A provider treating someone with Japanese heritage might start a depression medication at half the usual dose.

This is the future of medicine—not one-size-fits-all, but one-size-fits-your-genome. And it’s already here. The posts below show how these real-world differences play out in everyday care: from QT-prolonging drugs that hit certain groups harder, to how fiber supplements can interfere differently based on metabolism, to why some people need completely different dosing for the same condition. You’ll see what works, what doesn’t, and why your background matters more than you think.

Ethnicity and Drug Response: How Genetics Shape Medication Effectiveness

Harrison Greywell Dec, 1 2025 13Ethnicity influences how people respond to medications due to genetic differences in drug metabolism. Learn how CYP enzymes, pharmacogenomics, and ancestry impact drug effectiveness and safety across populations.

More Detail