Ethnicity and Drug Response: How Genetics Shape Medication Effectiveness

Dec, 1 2025

Pharmacogenomic Dosing Calculator

Warfarin Dosing Calculator

This tool demonstrates how genetics and ethnicity affect warfarin dosing. Not medical advice - for educational purposes only.

When a doctor prescribes a pill, they assume it will work the same way for everyone. But that’s not true. For some people, a standard dose of a blood pressure drug might do almost nothing. For others, the same dose could cause dangerous side effects. Why? Because ethnicity and drug response aren’t just social labels-they’re tied to real, measurable differences in how our bodies process medicine.

Why Some Drugs Work Better for Some People

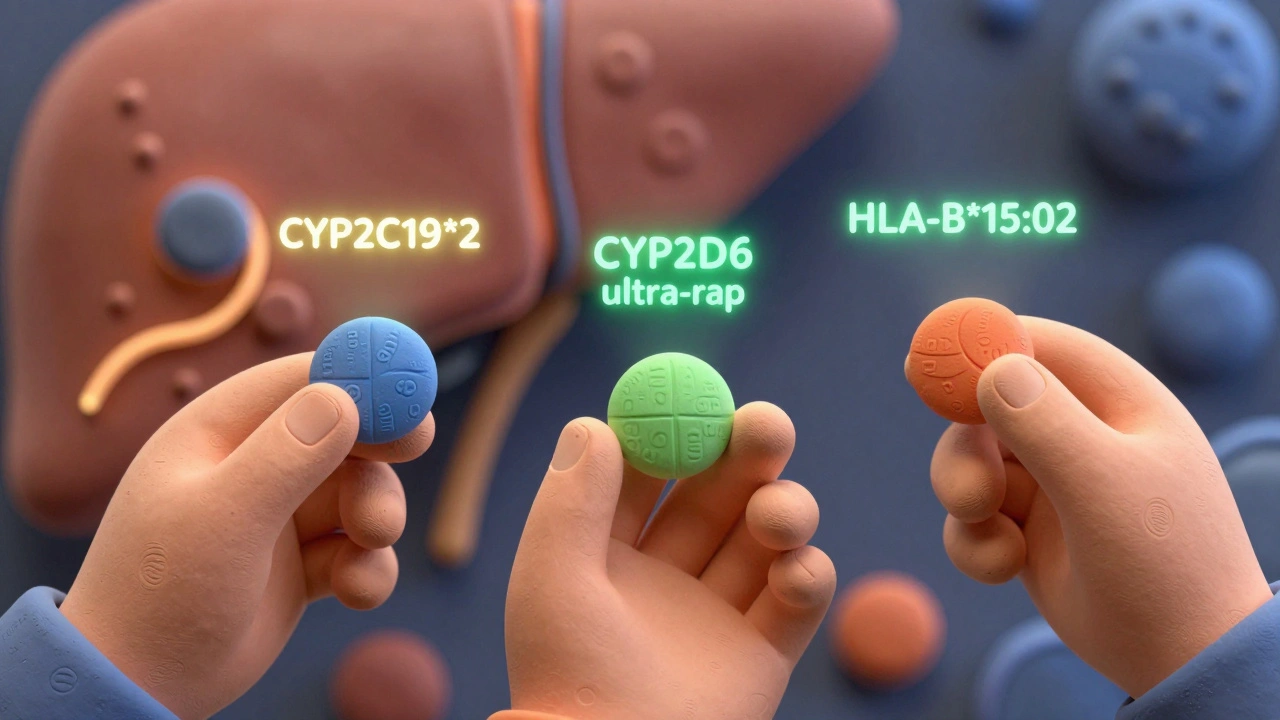

It’s not about skin color. It’s not about where your ancestors came from. It’s about genes. And those genes vary across populations in ways that directly affect how drugs are broken down, absorbed, and used by the body. Take clopidogrel, a common blood thinner given after heart attacks. About 15 to 20% of East Asians carry a genetic variant called CYP2C19*2. This variant makes their liver unable to activate the drug properly. So, even if they take the full dose, their blood doesn’t thin enough. In contrast, only 3 to 8% of European Americans have this variant. That means a standard dose might save a life in one group-and do nothing in another. The same goes for warfarin, the old-school anticoagulant. European Americans typically need about 20% less than African Americans to reach the same blood-thinning effect. Why? Because African Americans are more likely to carry variants in the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes that change how the drug is metabolized. Give them the same dose as a white patient, and they’re at risk of dangerous clots. Give them too little, and they bleed.The CYP Enzymes: Your Body’s Drug Detox System

The liver has a team of enzymes that break down most medications. The biggest players? The cytochrome P450 family-especially CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. These enzymes handle about 70% of all prescription drugs, from antidepressants to statins to painkillers. Here’s the catch: these enzymes aren’t the same in everyone. Some people have genes that make them slow metabolizers. Others have genes that make them ultra-fast. And these gene versions aren’t spread evenly across ethnic groups. For example:- CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers: 10-20% of North Africans and Middle Easterners, but only 1-2% of East Asians.

- CYP2C19 poor metabolizers: 15-20% of East Asians, 2-5% of African Americans.

- CYP2D6 poor metabolizers: 5-10% of Europeans, but less than 1% of East Asians.

Real-World Examples: Drugs That Work Differently by Ethnicity

Some drugs have been approved specifically for certain ethnic groups-not because of bias, but because the science demanded it. In 2005, the FDA approved a combination drug called BiDil (isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine) for heart failure in self-identified Black patients. Why? Clinical trials showed that Black patients on this drug had a 43% lower death rate compared to those on standard therapy. But here’s the twist: about 35% of Black patients still didn’t respond. And some white patients responded just as well. The drug wasn’t meant for “Black people.” It was meant for people with a specific combination of genetic and physiological traits that happen to be more common in that population. Another example: carbamazepine, used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder. In Han Chinese, Thai, and Malaysian populations, about 1 in 10 people carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene. If they take carbamazepine, they have a 1,000-fold higher risk of developing a deadly skin reaction called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. In Europeans, Africans, and Japanese, this gene is almost never found. So in countries like Taiwan and Thailand, doctors test for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine. In the U.S., they often don’t. And that’s dangerous. Even asthma meds aren’t immune. The ADRB2 gene controls how your lungs respond to albuterol. In African populations, the variant that makes the drug less effective is present in 50-60% of people. In Europeans, it’s only 25-30%. So a Black child with asthma might need a different inhaler or higher dose than a white child with the same symptoms.

The Problem With Using Race as a Shortcut

It’s tempting to say, “Black patients get this drug. Asian patients get that one.” But race is a social category, not a biological one. Two people who both identify as “Black” could have vastly different genetic backgrounds-one with roots in Nigeria, another with roots in South Africa. Their DNA might be more different than either is from a white European. Dr. Sarah Tishkoff’s research showed that a Nigerian and a Khoisan person from southern Africa are genetically more different from each other than either is from a Swede. So using “Black” or “Asian” as a medical label is like using “European” to prescribe heart meds-meaningless without context. A 2021 study in Pharmacotherapy found three Asian patients who tested negative for HLA-B*15:02 but still had severe skin reactions to carbamazepine. That proves: even within ethnic groups, you can’t assume safety based on race alone.The Future Is Genetic Testing, Not Guesswork

The medical community is slowly shifting away from ethnicity-based prescribing and toward genetic testing. The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) now has 27 gene-drug guidelines. Some hospitals, like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt, have been genotyping tens of thousands of patients for over a decade. Their results? Up to a 35% drop in adverse drug reactions. The FDA now requires drug companies to include genetic data in clinical trials. In 2022, 78% of new drug applications included pharmacogenomic data-up from 42% in 2015. And in 2023, the American Heart Association officially recommended moving from race-based to genotype-based dosing for blood thinners and antiplatelet drugs. The All of Us Research Program, run by the NIH, is building the largest and most diverse genomic database in history-with 80% of its 3.5 million participants from racial and ethnic minorities. That’s changing everything. Instead of guessing based on skin color, doctors will soon be able to say: “Your CYP2C19 status is *2/*2. Don’t take clopidogrel. Try ticagrelor instead.”

What’s Holding Us Back?

The science is ready. The tools exist. But adoption is slow. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals offer comprehensive pharmacogenetic testing. The test costs $1,200 to $2,500. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. Many doctors haven’t been trained to interpret the results. A 2022 study found clinicians need 8 to 12 hours of training just to understand the reports. And then there’s the data gap. Only 19% of participants in global genome studies are non-European. That means most of the genetic references we use to interpret tests were built on white populations. So when a Black or Indigenous patient gets tested, the system might misread their results because the reference data doesn’t match their ancestry.What You Can Do

If you’re a patient:- Ask your doctor: “Has my genetic profile been considered for this medication?”

- If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug, report it-and ask if genetic testing might help explain why.

- Know your family history: Did a relative have a severe reaction to a common drug? That’s a red flag.

- Stop using race as a proxy for genetics. Use it as a starting point for deeper investigation.

- Learn the CPIC guidelines. They’re free and publicly available.

- Push for testing access in your clinic. Even one test can prevent a life-threatening reaction.

It’s Not About Race. It’s About Your DNA.

Ethnicity and drug response aren’t about stereotypes. They’re about biology. And biology doesn’t care about labels. It cares about genes. The future of medicine isn’t “one size fits all.” It’s “one size fits one.” And that future is already here-for those who have access to it. The challenge now isn’t whether these differences exist. It’s whether we’re willing to stop guessing and start testing.Why do some drugs work better for certain ethnic groups?

Certain ethnic groups have higher frequencies of genetic variants that affect how drugs are metabolized. For example, East Asians are more likely to carry the CYP2C19*2 variant, which makes clopidogrel less effective. African Americans often carry CYP2C9 variants that require lower warfarin doses. These differences are rooted in population genetics, not race itself.

Is race a reliable predictor of drug response?

No. Race is a social construct and an imperfect proxy for genetics. While some drug responses cluster in certain populations due to shared ancestry, there’s massive variation within groups. Two people of the same race can have completely different genetic profiles. Genetic testing is far more accurate than racial categorization.

What drugs have known ethnic differences in response?

Common examples include: clopidogrel (less effective in East Asians), warfarin (higher doses needed in African Americans), carbamazepine (risk of severe skin reactions in Han Chinese), and beta-blockers (reduced blood pressure effect in African Americans). The FDA has issued specific labeling for some, like BiDil for heart failure in Black patients.

Can genetic testing prevent bad drug reactions?

Yes. Testing for genes like HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine prevents life-threatening skin reactions in high-risk populations. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have shown up to 35% fewer adverse drug events when pharmacogenetic testing is used routinely.

Why isn’t genetic testing more common in clinics?

Cost (typically $1,200-$2,500), lack of insurance coverage, limited access in community hospitals, and insufficient clinician training are the main barriers. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals offer comprehensive pharmacogenetic testing. Widespread adoption requires policy changes, funding, and education.