Allergic Disorders and Weight Gain: Why You Might Be Packing on Pounds

Oct, 17 2025

Allergy-Weight Connection Assessment

How Allergies Might Be Affecting Your Weight

Answer a few questions to identify which mechanisms from the article might be most relevant to your situation and get personalized recommendations.

How This Works

This assessment uses key mechanisms described in the article to help you understand how your allergies might be affecting your weight.

Based on your responses, we'll identify which factors may be most relevant to you and provide personalized recommendations.

Personalized Assessment Results

Recommended Actions

Ever wonder why, despite watching what you eat, the scale keeps creeping up? The answer might hide in your body’s allergic disorders a group of immune‑system reactions to otherwise harmless substances that can trigger symptoms like sneezing, itching, or digestive upset. Recent research shows a surprising link between these conditions and Weight Gain the net increase in body mass caused by excess calorie storage, hormonal shifts, or metabolic changes. Below we break down the science, share real‑world examples, and give you practical steps to keep both allergies and the waistline in check.

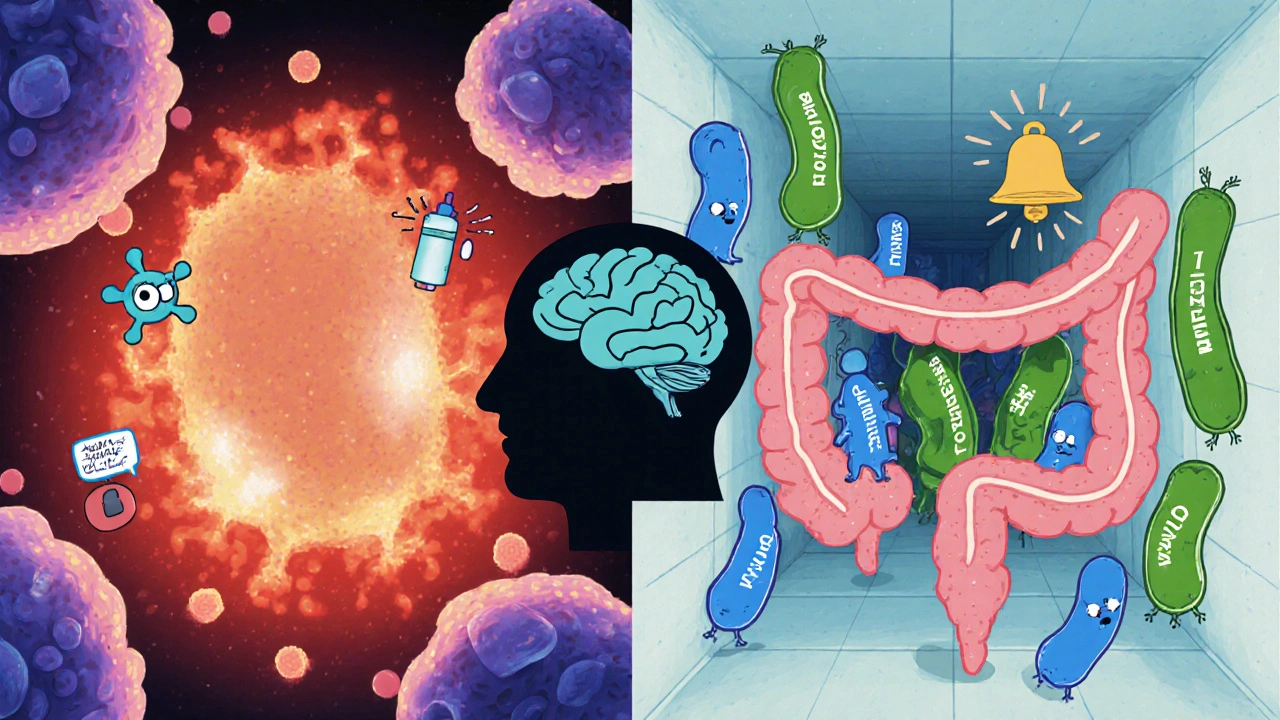

How the Immune System Talks to Your Metabolism

When an allergy flares, your immune system releases a flood of chemicals: histamine, cytokines, and other messengers. These aren’t just for battling the perceived invader; they also reach the brain and fat cells, nudging them to store more energy. Think of it as a built‑in survival mode-your body assumes a threat and prepares by hoarding calories. This cross‑talk is especially strong in chronic conditions like asthma, eczema, or persistent food sensitivities.

Histamine’s Role in Appetite and Fat Storage

Histamine gets a bad rap for causing itchy eyes, but it also regulates hunger. In small doses, it suppresses appetite by acting on the hypothalamus. However, chronic allergy sufferers often have a constant high‑histamine environment that leads to receptor desensitisation. The result? The appetite‑blocking signal fizzles out, and you feel hungrier more often.

Studies from the University of Pennsylvania (2023) measured plasma histamine in participants with seasonal allergies and found a 27% increase in daily caloric intake during peak pollen weeks compared to off‑season periods.

Chronic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance

Inflammation is the body’s alarm system. When allergies trigger low‑grade inflammation day after day, it can impair the way insulin works. Insulin resistance forces the pancreas to pump out more insulin, a hormone that also promotes fat storage, especially around the abdomen.

One longitudinal study followed 1,200 adults with allergic rhinitis for five years. Those with persistent symptoms developed insulin resistance at twice the rate of symptom‑free peers, and their average waist circumference grew by 3.2 cm.

Hormonal Disruption: Leptin, Cortisol, and Stress

Leptin-your body’s “fullness” hormone-often gets tangled up with allergy‑related inflammation. Elevated inflammatory markers can blunt leptin signaling, making the brain think you’re still hungry even after a full meal.

Stress hormones also join the party. Allergic flare‑ups are stressful events, spiking cortisol. High cortisol encourages the body to store visceral fat and can trigger cravings for sugary, high‑fat foods. A 2022 cortisol‑tracking experiment showed that participants with eczema had a 15% higher nightly cortisol surge during flare periods.

Gut Microbiome Shifts from Allergies

Your gut houses trillions of microbes that help digest food, regulate immunity, and even influence weight. Allergic reactions-especially food‑related ones-can disrupt this delicate ecosystem. When the gut flora tilts toward “pro‑inflammatory” species, the body becomes more efficient at extracting calories from food, a phenomenon known as the “energy harvest” effect.

Research published in Microbiome Journal (2024) compared stool samples from people with peanut allergies to non‑allergic controls. The allergic group had a higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes, a pattern linked to obesity in multiple studies.

Real‑World Examples: Food Allergies, Asthma, and Eczema

- Food allergies: Avoiding trigger foods often leads people to substitute high‑calorie, low‑nutrient alternatives. A child with a dairy allergy might switch to sweetened soy drinks, adding extra sugars and fats.

- Asthma: Inhaled steroids, a common asthma treatment, can raise appetite and promote weight gain when used long‑term.

- Eczema: Persistent itching disrupts sleep, and sleep loss is a well‑known driver of increased hunger hormones (ghrelin) and decreased satiety hormones (leptin).

These stories illustrate that the weight‑gain link isn’t just theoretical-it shows up in everyday decisions and medical treatments.

Practical Strategies to Manage Weight While Dealing with Allergies

- Identify and eliminate triggers: Work with an allergist to pinpoint foods or airborne allergens that set off your immune response. Reducing flare‑ups cuts down chronic inflammation.

- Choose anti‑inflammatory foods: Incorporate omega‑3‑rich fish, leafy greens, and turmeric. These help calm the immune system and improve insulin sensitivity.

- Watch histamine levels: Some fermented foods (kimchi, aged cheese) are high in histamine. If you’re sensitive, opt for fresh, low‑histamine meals.

- Maintain regular sleep patterns: Aim for 7‑9 hours. Good sleep balances cortisol and leptin, reducing cravings.

- Exercise strategically: Moderate cardio reduces systemic inflammation, while strength training preserves muscle mass and boosts metabolic rate.

- Consider probiotic support: Strains like Lactobacillus rhamnosus have shown promise in both allergy symptom reduction and weight management.

- Monitor medication side effects: If you’re on oral steroids or certain antihistamines, discuss weight‑friendly alternatives with your doctor.

Quick Checklist: Spotting the Allergy‑Weight Connection

- Frequent flare‑ups coincide with seasonal weight gain?

- Do you notice increased appetite during allergy season?

- Is there a family history of both allergies and obesity?

- Are you on medications known to affect metabolism (e.g., steroids)?

- Do you experience sleep disturbances when symptoms flare?

If you answered “yes” to several of these, it’s worth exploring the allergy‑weight link with a healthcare professional.

Key Mechanisms Connecting Allergic Disorders to Weight Gain

| Mechanism | Biological Pathway | Weight‑Related Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Histamine Desensitisation | Reduced hypothalamic appetite suppression | Increased calorie intake |

| Chronic Inflammation | Cytokine‑induced insulin resistance | More fat storage, especially abdominal |

| Hormonal Imbalance | Elevated cortisol, blunted leptin signaling | Higher stress‑eating, visceral fat |

| Gut Microbiome Shift | Increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio | Greater energy harvest from food |

| Medication Side Effects | Steroid‑induced appetite rise | Weight gain independent of diet |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can allergic disorders cause weight gain even if I don’t change my diet?

Yes. The inflammation and hormonal shifts triggered by chronic allergies can boost appetite, reduce metabolic rate, and encourage the body to store fat, all without any extra calories.

Are antihistamines linked to weight gain?

First‑generation antihistamines (like diphenhydramine) can cause drowsiness, leading to reduced activity and occasional weight gain. Newer, non‑sedating antihistamines have a much lower risk.

Should I avoid all high‑histamine foods if I’m trying to lose weight?

If you’re histamine‑intolerant, limiting aged cheeses, cured meats, and fermented products can help control appetite spikes. Otherwise, focus on overall calorie balance and anti‑inflammatory choices.

How long does it take to see weight changes after allergy treatment?

Most people notice reduced cravings and better energy levels within 4-6 weeks of consistent allergy management, though measurable weight loss may take longer depending on diet and activity.

Is there a link between eczema and obesity in children?

Yes. Studies show children with moderate‑to‑severe eczema have a 1.7‑fold higher risk of becoming overweight, partly due to sleep disruption and steroid cream use.