Barrett’s Esophagus – What It Is and Why It Matters

If you’ve heard doctors mention “Barrett’s” while talking about heartburn, they’re warning you about a change in the lining of your esophagus. Basically, long‑term acid reflux (GERD) can turn normal squamous cells into columnar cells that look more like intestinal tissue. That’s Barrett’s esophagus. It isn’t cancer, but it raises the odds of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma down the road, so catching it early is key.

How Barrett’s Happens and Who Gets It

The main trigger is chronic acid exposure. If you’ve been dealing with daily heartburn for years, especially after big meals or late‑night snacks, your esophagus is under constant attack. Other risk factors include being male, over 50, overweight, smoking, or having a family history of Barrett’s or esophageal cancer. Not everyone with GERD gets Barrett’s, but the longer the reflux lasts, the higher the chance.

Finding Out If You Have It

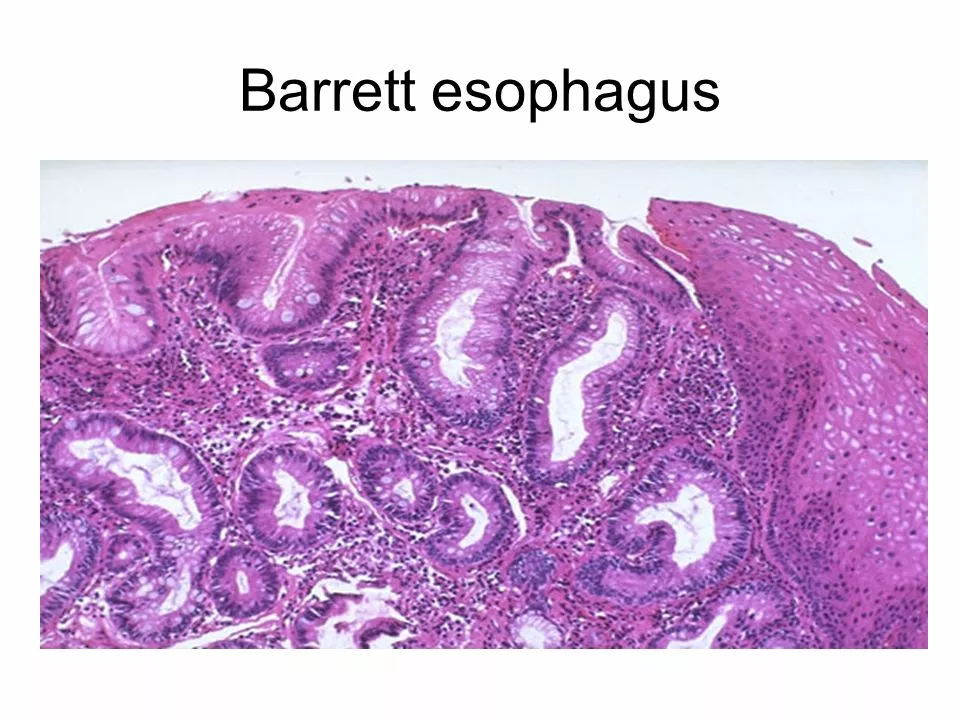

The only way to know for sure is an upper endoscopy. During the procedure a tiny camera slides down your throat and looks at the lining. If doctors see suspicious patches, they’ll take a biopsy – a small tissue sample sent to a lab. The results tell whether the cells have changed and if any dysplasia (pre‑cancer changes) is present. Most people need an endoscopy every 3–5 years if no dysplasia is found.

Symptoms aren’t reliable on their own. Many folks with Barrett’s feel just ordinary heartburn, chest discomfort, or a sour taste. Some notice difficulty swallowing or a feeling of food getting stuck. Because those signs overlap with plain GERD, don’t rely on them alone – ask your doctor about an endoscopy if you have persistent reflux.

Once diagnosed, treatment focuses on two goals: control acid and monitor the lining. Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the go‑to meds for reducing stomach acid. Lifestyle tweaks help a lot too: lose excess weight, avoid big meals before bed, raise the head of your bed, cut back on coffee, alcohol, chocolate, and spicy foods.

If biopsies show low‑grade or high‑grade dysplasia, doctors may recommend more aggressive steps. Endoscopic therapies like radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can burn away abnormal cells, letting healthy tissue grow back. In rare cases with advanced cancer risk, surgery to remove part of the esophagus might be advised.

Living with Barrett’s means staying on top of follow‑up appointments. Keep a symptom diary – note when heartburn spikes, what you ate, and any new swallowing problems. Share that info with your gastroenterologist; it helps decide if another endoscopy is needed sooner.

Bottom line: Barrett’s esophagus is a warning sign, not a death sentence. Controlling reflux, quitting smoking, staying active, and regular monitoring can keep the cancer risk low. If you’re worried about long‑standing heartburn, talk to your doctor about an endoscopy – early detection makes all the difference.

How Esomeprazole Can Help Treat Barrett's Esophagus

Harrison Greywell May, 27 2023 5As a blogger, I recently discovered how Esomeprazole can be a game changer for those suffering from Barrett's Esophagus. This proton pump inhibitor not only reduces stomach acid production, but also helps heal the damaged esophageal lining. In turn, this minimizes the risk of developing esophageal cancer, a major concern for Barrett's Esophagus patients. Furthermore, Esomeprazole is known to provide relief from heartburn and acid reflux symptoms. Overall, this medication can significantly improve the quality of life for those dealing with this challenging condition.

More Detail