Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis: Understanding Muscle Inflammation and Modern Treatment Options

Nov, 20 2025

Dermatomyositis and polymyositis are rare autoimmune diseases that attack your skeletal muscles, causing progressive weakness and, in the case of dermatomyositis, a distinctive skin rash. These conditions don’t show up on routine blood tests, and many people are misdiagnosed for years-sometimes seeing four or more doctors before getting the right answer. If you’ve been told you have "just fatigue" or "fibromyalgia" but your muscles keep getting weaker, especially when climbing stairs or standing up from a chair, it’s worth digging deeper.

What Sets Dermatomyositis Apart from Polymyositis?

At first glance, both conditions look similar: symmetrical weakness in the muscles closest to your trunk-hips, shoulders, neck, and thighs. You might struggle to lift your arms, get out of a low chair, or even swallow food. But the key difference is skin.

Dermatomyositis comes with visible signs. A purple or reddish rash often appears on your eyelids-called a heliotrope rash-or over your knuckles, elbows, and knees. This isn’t just a cosmetic issue; it’s a marker of the disease’s underlying mechanism. While polymyositis is driven by T-cells attacking muscle fibers directly, dermatomyositis involves B-cells and antibodies attacking the small blood vessels feeding the muscle. That’s why skin and lungs are often affected in dermatomyositis, but rarely in polymyositis.

Another major difference: dermatomyositis can appear in children (ages 5-15) and adults (40-60), while polymyositis almost never occurs before adulthood. And here’s something critical-about 1 in 5 adults with dermatomyositis have an undiagnosed cancer. That’s why doctors screen for ovarian, lung, or gastrointestinal cancers right after diagnosis. Polymyositis doesn’t carry that same risk.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis is a puzzle made of blood work, imaging, and a muscle biopsy.

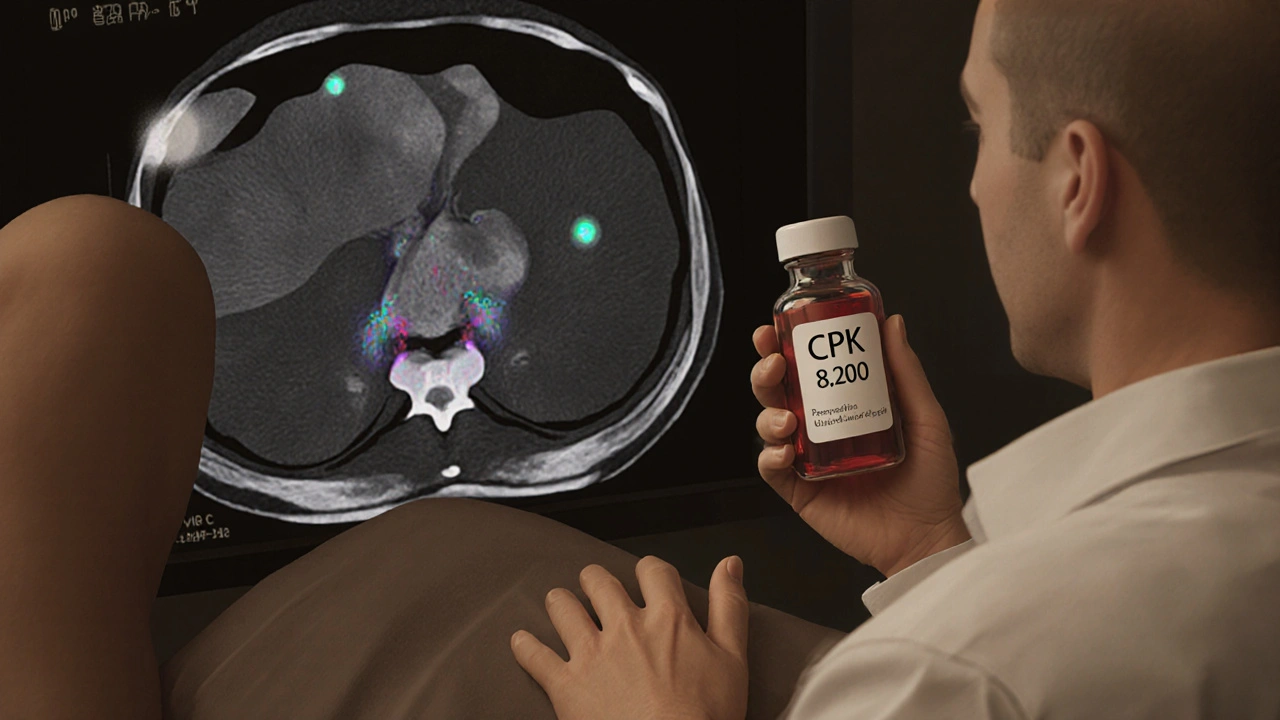

Blood tests usually show high levels of creatine phosphokinase (CPK), often 5 to 10 times above normal (normal range: 10-120 U/L). Other markers like ESR and CRP signal inflammation. Autoantibodies-like anti-Jo-1 or anti-Mi-2-are found in about 60% of cases and help classify the disease subtype. But even if antibodies are negative, the disease can still be present.

An electromyography (EMG) picks up abnormal electrical activity in weakened muscles. MRI can show swelling and inflammation patterns, helping doctors decide where to biopsy. But the gold standard is the muscle biopsy. In polymyositis, you’ll see T-cells surrounding muscle fibers that aren’t dead yet. In dermatomyositis, the damage shows up as "perifascicular atrophy"-a pattern where muscle fibers at the edges of bundles shrink and die, while the center stays intact. This distinction is why biopsy matters more than blood tests alone.

It takes 3 to 6 months on average to get a confirmed diagnosis. Many patients wait over two years. Misdiagnosis is common-30% of cases are initially labeled as fibromyalgia, lupus, or thyroid issues. If you’re not getting better after standard treatments for those, push for a rheumatology referral.

First-Line Treatment: Steroids and Their Costs

Corticosteroids like prednisone are the starting point for both conditions. Doctors typically begin with 1 mg per kilogram of body weight daily-around 40 to 60 mg for most adults. The goal is to shut down inflammation fast. Within 4 to 8 weeks, you should see improvement in strength and CPK levels.

But steroids come with a heavy price. Half of long-term users develop osteoporosis. One in three get diabetes. Two in five develop cataracts. Weight gain is nearly universal, along with insomnia and mood swings. That’s why tapering is slow-often taking 12 to 24 months-and why doctors add calcium, vitamin D, and bone-strengthening drugs like bisphosphonates from day one.

One patient on Reddit shared: "After 9 months on 40 mg of prednisone with no real improvement, my doctor added methotrexate. Four months later, my CPK dropped from 8,200 to 450. I cut my steroid dose in half." That’s the pattern: steroids get you in the door, but they’re not the finish line.

Second-Line Therapies: What Comes Next?

If steroids aren’t enough-or if side effects become unbearable-doctors turn to immunosuppressants. Methotrexate is the most common next step. Azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are also used, especially if you have lung involvement.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a powerful option for dermatomyositis patients who don’t respond. It’s expensive and requires weekly infusions, but studies show it improves skin rashes and muscle strength in 60-70% of resistant cases. It’s less effective for pure polymyositis.

Rituximab, a drug used for rheumatoid arthritis and lymphoma, has shown promise in small trials. A 2011 study found 60-70% of refractory patients improved. It’s not FDA-approved for myositis, but many rheumatologists use it off-label when other options fail.

Newer drugs are emerging. JAK inhibitors like tofacitinib, used for arthritis, showed 65% improvement in skin symptoms and 52% in muscle strength in a 2023 trial. Abatacept, which blocks T-cell activation, is being tested for polymyositis and early results are encouraging. These aren’t widely available yet, but they represent the future of targeted therapy.

Physical Therapy: The Hidden Key to Recovery

Rest won’t fix this. In fact, staying inactive makes weakness worse. Physical therapy isn’t optional-it’s essential. Starting within two weeks of diagnosis can mean the difference between regaining independence and needing a wheelchair.

Therapy focuses on low-resistance, high-repetition exercises: seated leg lifts, wall push-ups, walking on flat ground. The goal isn’t to build bulk but to prevent muscle atrophy and maintain joint mobility. A 2022 study from the Hospital for Special Surgery found patients who stuck with a structured program improved functional capacity by 35-45% in six months.

But many patients skip therapy because they’re too tired or think it’s "too hard." Don’t. Fatigue is a symptom of the disease, not a reason to stop moving. Even 15 minutes a day of gentle movement helps. A physical therapist will tailor the program to your strength level and adjust as you improve.

Living With the Disease: Daily Challenges

It’s not just about muscle weakness. About 40% of dermatomyositis patients develop interstitial lung disease-scarring in the lungs that causes shortness of breath. That requires regular lung function tests and sometimes additional medications.

Dysphagia, or trouble swallowing, affects 15-30% of patients. It’s not always obvious. You might choke on liquids, feel food sticking in your throat, or have frequent pneumonia. A speech pathologist can help with swallowing exercises and dietary changes.

Fatigue hits hard. In a 2022 survey of over 1,200 patients, 68% said fatigue limited their daily life more than muscle weakness. Sleep is often disrupted by steroid side effects, pain, or anxiety. Managing sleep hygiene and mental health is part of treatment.

Insurance is another hurdle. Many second-line drugs require prior authorization, and delays average 17 days. Some patients stop treatment because they can’t afford the co-pays. Patient advocacy groups like Myositis Support and Understanding offer help navigating insurance and finding financial aid.

Prognosis: Hope in the Numbers

Twenty years ago, half of people with these diseases died within 10 years. Today, 80-85% survive that long. Why? Earlier diagnosis. Better drugs. Aggressive therapy.

Patients who start treatment within the first six months of symptoms have an 80% chance of reaching low disease activity or remission. That’s not a cure-but it’s a life where you can work, drive, play with your kids, and walk without help.

Regular monitoring is key. Blood tests every 4-8 weeks, muscle strength checks using the MMT-8 scale, and lung function tests every 6 months. Keep track of your symptoms. If you notice new rashes, coughing, or trouble swallowing, tell your doctor right away.

What’s Changing Now?

In June 2023, the European League Against Rheumatism updated its diagnostic criteria to include myositis-specific antibodies as core markers. This means faster, more accurate diagnosis-potentially cutting delays by 30-40%.

Research is shifting from broad immunosuppression to precision medicine. We now know that different antibody profiles (anti-synthetase, anti-MDA5, etc.) predict different outcomes and responses to treatment. In the next five years, your treatment may be chosen based on your antibody profile, not just your symptoms.

But there’s still a shortage of specialists. With only about 5,800 rheumatologists in the U.S. for 58 million people with autoimmune conditions, access is a problem. If you’re in a rural area, telehealth with a rheumatologist may be your best option.

And while the global market for myositis drugs is growing-projected to hit $2.1 billion by 2029-only three drugs are officially approved for dermatomyositis, and none for polymyositis. Most treatments are used off-label. That’s why patient advocacy matters. Push for research. Join registries. Your voice helps drive change.

Can dermatomyositis or polymyositis be cured?

No, there is no cure yet. But with early, aggressive treatment, most patients achieve long-term remission or low disease activity. Many return to normal daily activities, including work and exercise. The goal isn’t to eliminate the disease completely, but to control it so it doesn’t control your life.

Is muscle weakness from these diseases permanent?

Not always. If treated early, muscle strength can recover significantly. But if inflammation goes on for years without treatment, muscle tissue can be replaced by scar tissue, leading to permanent weakness. That’s why starting treatment within six months of symptoms is critical. Delayed treatment increases the risk of irreversible damage.

Can children get polymyositis?

No. Polymyositis only affects adults. Children who develop muscle weakness with a rash have juvenile dermatomyositis, which is treated differently than the adult form. Juvenile dermatomyositis often has more skin involvement and a higher risk of calcinosis (calcium deposits under the skin), but children tend to respond better to treatment than adults.

Do I need to avoid the sun if I have dermatomyositis?

Yes. Sun exposure can worsen the skin rash and trigger disease flares. Use broad-spectrum sunscreen with SPF 50+, wear wide-brimmed hats, and avoid direct sunlight between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Even on cloudy days, UV rays can penetrate. Some patients report rashes flaring after minimal sun exposure, so protection isn’t optional-it’s part of your treatment plan.

Why do I need a muscle biopsy if my blood tests are high?

High CPK levels can happen in many conditions-intense exercise, trauma, thyroid disorders, even some medications. A biopsy confirms the inflammation pattern is autoimmune and rules out other muscle diseases like inclusion body myositis or muscular dystrophy. It also helps distinguish dermatomyositis from polymyositis, which affects treatment choices. Blood tests tell you something’s wrong; the biopsy tells you what it is.

Can I still exercise with these conditions?

Yes-but carefully. Avoid high-intensity workouts, heavy weights, or activities that cause pain. Low-resistance exercises like walking, swimming, or using resistance bands are safe and beneficial. Working with a physical therapist who understands autoimmune myopathies is essential. Exercise reduces fatigue, improves mood, and helps maintain independence. Inactivity makes things worse.

What should I do if I develop a cough or shortness of breath?

Tell your doctor immediately. About 30-40% of dermatomyositis patients develop interstitial lung disease, which can progress silently. Early detection through lung function tests and CT scans can prevent severe scarring. If caught early, medications like corticosteroids or immunosuppressants can stabilize or even reverse lung damage. Don’t wait for it to get worse.

Next Steps: What to Do Now

If you suspect you or someone you know has dermatomyositis or polymyositis, start with your primary care doctor. Ask for blood tests: CPK, ESR, CRP, ANA. If results are abnormal or symptoms persist, demand a referral to a rheumatologist. Don’t accept "it’s just aging" or "you’re stressed."

Keep a symptom journal: note when weakness worsens, any new rashes, swallowing issues, or breathing changes. Bring it to your appointment. It helps doctors see patterns.

Connect with support groups. The Myositis Association and Myositis Support and Understanding offer forums, webinars, and patient advocacy tools. You’re not alone-and learning from others’ experiences can save you months of missteps.

And remember: this isn’t a death sentence. With the right care, most people live full, active lives. The key is acting fast, staying informed, and never giving up on finding the right team to help you through it.